ANGLO- AMERICAN PUBLISHING Co. Location: 172 John Street, Toronto, Ontario. Owner: Sinnott News Ltd. President & Business Manager: Thomas Harold Sinnott. Managing Editor: John McKellar Calder. Secretary-Treasurer: John Gordon Baker. Production and Circulation Manager: Edmund Christie Johnston.

Employees a partial list: June Banfield, Eva Davies (Married name Koller), Les Gilpin, Malcolm Fleming, Ed Furness, Priscilla Hutchings, Jean McMaster, Betty Mercer, Jean Townsend .

Independent Contributors: Ted McCall, J. R. McLeod, Doris Slater.

Characters: Circus Capers, Clip Thomson & Tub, Commander Steel, The Crusaders, Doctor Destine, Don Shield and His Revrso-Ray, Freelance, Martin Blake The Animal King, Men of the Mounted, Michael Lee British Secret Service, Pat The Air Cadet, Purple Rider, Red Rover, Robin Hood, Sooper Dooper, Terry Kane. .

Features: Stamp Stories, appeared in Three Aces, 1-2, January/February 1942: 2-3.

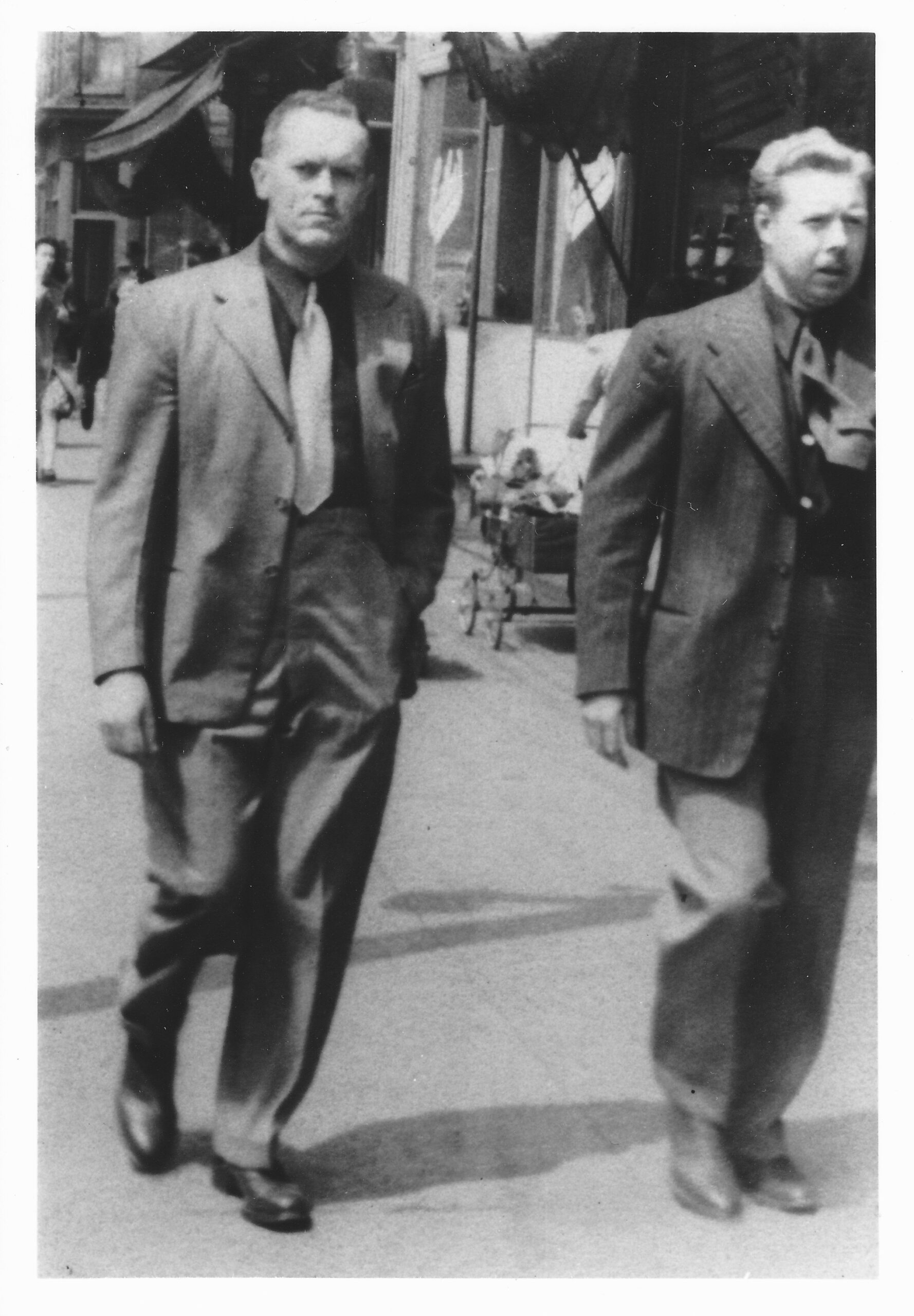

From left to right, Ed Furness, Jack Calder, Les Gilpin in Jack Calder’s back yard circa 1944

This least investigated of all the Canadian comic book companies had the best chance of survival in the post World War Two North American market. It had made all the correct moves, created a line of original characters organized a stable and competent staff and successfully converted to colour before the American competition returned to Canada, but as we shall see its unsuccessful bid to gain a foothold in the American market doomed it.

Anglo-American was a subsidiary of Sinnott News. The financial part and the distribution were both handled by Sinnott News. To quote Ed Furness “… as far as we [staff of Anglo-American] were concerned Sinnott News was just on the other side of the wall.”

It was initiated because of the cancellation of a cartoon adventure strip. The war put an end to Ted McCall’s Robin Hood and Company which was appearing in about 80 newspapers, but the resourceful Ted who was an editor at the Evening Telegram [Toronto] jumped at the opportunity the Canadian government’s just introduced War Exchange Act provided. The Act banned the importation of non-essential goods from the U.S. in order to preserve Canadian currency for the purchase of war materiel. Ted owned the copyright and the printing plates for the Robin Hood and Company strips. Why not he reasoned, reprint the plates in a tabloid? He took the idea to Harold Sinnott of Sinnott News, a Toronto based periodicals distribution company. Sinnott liked the proposal and Anglo-American Publishing Co. Ltd. was born, to publish reprints of the strip. The first issue appeared in March 1941. The tabloid format was quickly dropped, and the plates were cut and rearranged into a standard comic book size. The reprints lasted about a year, after which McCall picked up from where the strip had left off and began writing new material with Anglo-American staff doing the illustrations.

Ted and apparently Anglo-American were not about to stop with one title. He had another character in mind, one who would have no past and would fight the Nazi behind their own lines. He had discovered probably during his research on Robin Hood, that a knight whose sword was for hire, one who operated alone was a “freelance”. “Freelance” would be the name of his character. For this project he brought Ed Furness a commercial artist on board. In July 1941, four months after the appearance of Robin Hood & Company, Anglo-American’s second publication Freelance, appeared on the newsstands. It was a sixty-four-page periodical, devoted entirely as it always would, to the adventures of Ted’s hero.

Ted remained an editor at the Telegram and sent his scripts to Anglo-American. Ed Furness initially remained with his regular job drawing “Freelance” on the side. Once he felt this new project was secure, he quit that job and joined Anglo-American where he met Les Gilpin and Jack Calder.

Left to right, Les Gilpin, Ed Furness, circa 1943-44.

Left to right, Les Gilpin, Ed Furness, circa 1943-44.

So far, Anglo-American depended on Ted’s fertile imagination. This situation changed with the publication of Three Aces in November 1941. It featured “Michael Lee British Secret Service”, “Martin Blake The Animal King”, “Circus Capers” and “Sooper Dooper”. “Michael Lee” is credited to Jay McKellar a pseudonym for Jack Calder, but since there is no evidence that Calder had any illustrative skills, it is likely he partnered with Les Gilpin as he did for “Sooper Duper”. “Circus Capers” has no credits but it was likely done by Les Gilpin or J.R. McLeod, who apparently was employed by the company or freelanced for it only a short time. “Martin King” is credited to Doris Slater, but it is likely she partnered with her brother-in-law Ted McCall to produce it.

Three Aces was followed by Grand Slam which appeared in December, also an inhouse production. Grand Slam featured “The Crusaders”, “Pat The Air Cadet”, “Don Shield and His Reverso-ray” and “Clip Thomson and Tub”. “The Crusaders” has no credit but was the work of Les Gilpin. “Pat The Air Cadet” is credited to McDuff but was probably another partnership between Ted and Doris. “Don Shield” was an Ed Furness creation, his first as a cartoonist. J.R. McLeod was responsible for the short lived “Clip Thomson”.

Anglo-American continued to expand at a ferocious rate, but it did so by importing characters from Fawcett Publications Sinnott News Ltd.’s U.S. associate from whom before the war it had imported all types of periodicals. The arrangement was beneficial for both companies. Anglo-American was able to expand its line and Fawcett was able to keep its characters exposed in Canada. Anglo-American published Captain Marvel and Whiz Comics in January 1942 and Spy Smasher in June of the same year. These were Fawcett titles filled with Fawcett characters but as we shall see not copies of Fawcett publications. In only ten months Anglo-American had expanded from one to seven periodicals. According to Ed, “Freelance remained the star of Anglo-American with sales of about 40,000 copies per issue. “Captain Marvel” strangely enough did not sell well.

The War Exchange Act allowed the importation of scripts but prevented the importation not only of magazines but of printing plates for the magazines as well. It was, therefore, necessary for Anglo-American do the artwork for the Fawcett characters inhouse. This meant the Anglo-American cartoonists and illustrators not only had to work on Anglo-American creations but also handle the visual side of the imported scripts. To keep up with the publishing schedule, the workload for this small staff was tremendous. Ed put it this way, “Production is a hungry master. It just devours you.”.

To meet this hunger Anglo-American was hiring. Ed once quipped that if a person could hold a pencil they got a job, but conversations with others suggests that Anglo-American hired mainly from art colleges. It also appears they hired predominantly – almost exclusively – women. At the start, Anglo-American paid $5 per page, split among the various artists doing the page. This rate was later increased to $10 a page. Ed was paid a commission, and the royalty paid to Ted for writing was 1/10 of a cent per copy sold. The staff, with the lone exception of Ted, and probably Doris Slater worked in an office.

These newcomers of course had no experience in sequential art. To cope with this situation, Ed developed a system based on his animation experience. He laid out the pages. They were then given to Betty Mercer who did the lettering for Anglo-American’s entire output. The next person to receive the layouts penciled and inked the principal characters. The pages then moved to another illustrator who did secondary characters and finally went to Malcolm Fleming who did all the backgrounds. Nonetheless, the quality of illustration remained poor. The situation was so bad that for Ed it became a kind of nightmare. The low point came in 1942, when to maintain consistency in the facial features of the principal characters, Ed was forced to use stick-on heads. He drew the heads of the major characters in various sizes and positions and had them printed on sticky paper. The neophytes then had to draw only the body of the character and then attach the appropriate head. Out of this situation came the legend that Harold Town, later a famous painter, refused to use these decals and would employ tactics such as drawing the character with his back to the reader to avoid them. Mercifully, this procedure lasted only a few months. As the technique of the illustrators improved, Ed’s layouts became increasingly sketchy. As time passed, the approach embraced more and more of the company’s production until finally all the material, including Freelance, was done by this method. Indeed, as Ed reminisced, June Banfield and Priscilla Hutchings who began as inexperienced artists became so good they took over most of the finished art on Freelance. Jean McMaster, another art college graduate mentioned in an interview that she did the entire work on “Captain Marvel” except for lettering.

The system did not create the type of comic book art we see today, but it was good for overall quality control. By comparing the drawing result in “The Crusaders”, with that in “Flash Gordon” and “Buck Rogers”’ we can see the standard that the system achieved. The visual art in “The Crusaders” falls far short of the genius of Alex Raymond but is better than that in “Buck Rogers”. In short, the system did not achieve the heights that brilliant individual cartoonists could, but it produced work that ranked high among comic books in general. The system had several addition advantages. Illustrators were assigned the tasks they did best. Betty Mercer and Malcolm Fleming were responsible for lettering and backgrounds because they were most accomplished at these tasks. Likewise, Pricilla Hutchings concentrated on drawing women because this was her strength. As well the experienced staff were assigned the major tasks such as principal characters while the new members were assigned minor tasks less likely to affect the overall visual attractiveness of the panels. The system made it easier for neophytes to enter the business and develop their skills. There was an overall corporate style rather than distinctive of styles between the features. These features were a vital defense against staff turn over when it became critical in the industry.

Another feature of this fast expansion was the loss of some original characters. It is not surprising to see “Michael Lee” dropped from Three Aces as Jack Calder’s Managing Editor duties increased. In the cases of “Martin Blake” which it is suspected was written by Ted, and “Don Shield” cartooned by Ed, it is likely that as the reprints for both “Robin Hood” and “Men of the Mounted” came to an end both of these men had their hands full creating new episodes for those series. In addition, Ed was responsible for the breakdowns of Fawcett stories as well. The result, was Fawcett characters came to predominate in both Three Aces and Grand Slam.

This system lasted about two years, then on June 6, 1944, the Allies landed at Normandy. The defeat of Germany was coming although when was uncertain. The War Measures Act would eventually be lifted, and Sinnott News would again be able to directly import Fawcett periodicals. Was it these predictable events or was it that the staff had gained experience in sequential art and as said early Anglo-American’s own creations were selling better than Fawcett’s that the company introduced a wave of new inhouse characters. Probably a combination of both. In September 1944 “The Purple Rider” appeared in Three Aces followed shortly thereafter by “Terry Kane”. They joined “Sooper Dooper”. Also in September 1944, “Commander Steel”, “Red Rover” and “Dr. Destine” joined “Pat The Air Cadet” and replaced a variety of Fawcett characters including “Captain Marvel Jr.”, “Ibis” and “Golden Arrow” in Grand Slam. By the end of 1944 Grand Slam and Three Aces had returned to using only inhouse content. Anglo-American continued to draw the content for and publish the Fawcett titles Captain Marvel, Spy Smasher and Whiz Comics but they would be gone in about a year.

Ted McCall remained the most important creative factor at Anglo-American. His prolific writing completely filled two of Anglo-American’s periodicals Freelance and Robin Hood which included “Men of the Mounted”. In addition he influenced the creative output of other members of the Anglo-American creative team. “Commander Steel” who at first glance looks like “Captain Marvel” on closer reading is clearly a descendent from “Freelance” and “Red Rover”, a South seas adventurer also owed much to “Freelance”. Ted’s sources were R.C.M.P. cases and Robin Hood stories. Other influences used by other creators came from radio and film. None came from comic strips or comic books.

Anglo-American moved into merchandizing its characters. As Ed recalled: “I saw a kid with some kind of crest that glowed in the dark. I got the bright idea that we ought to put our characters on little pieces of cloth and sell them for a dime. I suggested it to Harold [Sinnott] and he said sure go ahead. So we did and the Monday morning mail usually brought in a mail bag of requests for glow crests and some poor kid back in the warehouse had to be stacking up these dimes and sorting out who wanted what and seeing that they got mailed back. They [the crests] were silk screened with fluorescent dyes.”

In the public relations field, the company supported the Boy Scouts and Cubs of Canada, putting in full page accounts of what Cubs and Boy Scouts were about. Scouts who won medals were honoured and wood-lore tips were included.

Early in 1945, a fortuitous event occurred that launched Anglo-American into colour. As Ed recalled, “The Globe and Mail which printed our comics, had bought a four-colour fountain for their daily press and Jimmy Harrison, who’s the superintendent, said to Harold Sinnott, ‘How’d you like to do your comics in colour?’ Well, of course, that was just fine.” Just fine indeed, with the War Exchange Conservation Act still in place, Anglo-American’s conversion to colour would make it a fox in the chicken coop that was the Canadian comics industry. It is wrong to assume that because U.S. comic books were kept out of Canada there was no competition. There were four major companies competing in the small Canadian market Anglo-American and Bell Features in Toronto, Educational Projects in Montréal and Maple Leaf Publications in Vancouver. In addition there was a revolving door of smaller publishers. Anglo-American’s first colour comics reached the newsstands in July 1945. By the following month, its entire line with the exception of the Fawcett titles was in colour, leaving Anglo-American not only with a competitive edge over its rivals but ready to match the product that would be coming from the U.S. Educational Projects never attempted to convert to colour. Its last issue of Canadian Heroes was October 1945, two months after Anglo-American converted to colour. The two other companies continued but only Bell Features had any success converting.

During the conversion period, Robin Hood and Freelance were initially combined into one periodical, Freelance/Robin Hood. Grand Slam and Three Aces were compressed into Grand Slam/Three Aces. This situation lasted about five months until the beginning of 1946 when the combined titles were broken apart to once again form Robin Hood, Freelance, Grand Slam and Three Aces. Coincident with introduction of colour Anglo-American dropped Spy Smasher after the May 1945 edition, Captain Marvel after the August 1945 edition and Whiz Comics after the October 1945 edition. Anglo-American had returned to publishing four periodicals featuring only staff-originated characters.

Germany surrendered to the Allies May 7,1945 and Japan surrendered September 2, 1945. While it is unlikely these two events prompted Anglo-American’s adoption of colour they almost certainly prompted the dropping of Fawcett characters and titles as Sinnott News would now be able to import them directly from Fawcett as the War Exchange Act was slowly dismantled. But Sinnott News was also preparing Anglo-American products for the U.S. market. It obtained U.S. copyrights for Anglo-American’s characters and applied for 2nd class entry into the U.S. at the Buffalo New York Post Office. According to Ed, negotiations were going on with Fawcett Publications for them to distribute such titles as Freelance in the U.S. “They were impressed by the success, in a relatively short time that “Freelance” had enjoyed …and thought it might take-off down there. The idea, I remember now, was they were going to turn Freelance into some sort of private eye. They did not have a private-eye among their comics, at least not one that was significantly popular.” It is likely the attempt was for Fawcett to expand its line distributing Anglo-American titles in the U.S. while Sinnott distributed Fawcett publications in Ontario. Negotiations fell through probably collateral damage in the copyright battle that had been raging between Fawcett and DC Comics since 1939. The court decisions were ambiguous and confusing. Ultimately, Fawcett decided to settle out of court with DC Comics and left the field completely in 1953. Ed was suddenly told by Sinnott that the operation was at an end shortly after he had been assured it would continue.

Anglo-American’s demise in late 1946 came as a shock to everyone who worked at the company. “See we thought this thing was going to go on forever.” Ed explained. Certainly Anglo-American had made all the correct moves. It had a stable and competent work force while other companies struggled to hold onto their freelance staff, successfully transferred to colour and developed a line of appealing characters. But the economics of the periodical publishing business made its lost bid to access the U.S. market fatal. The Canadian market at the end of World War Two was simply too small to support the Canadian companies plus the U.S. giants. The abundance of product available fragmented the market to the point where no company would be able to support its operations on the part of the Canadian market available to it, unless it could cover its major costs, creative, printing (especially in colour), administration in another market. That is what the American companies were able to do, cover their major costs in the giant U.S. market. They probably didn’t even have to increase their print runs to cover the miniscule Canadian market. They could service the Canada paying only distribution costs. To be able to compete, the Canadian companies would have had to use the same strategy, cover their major costs in the U.S. market and therefore be able to service their own market by paying only distribution costs. Yet neither Anglo-American nor any other Canadian company was able to penetrate the formidable U.S. distribution system.

As a postscript to this story, in 2016 Robert MacMillan came across a 1948 pocketbook god’s little acre by the U.S. author, Erskine Caldwell. It was a reprint published by Anglo-American Publishing Co. At that time, Fawcett was moving into pocketbooks. Was Anglo-American through its association with Fawcett making an attempt reinvent itself as a secondary publisher of pocketbooks? So far, this is the only evidence that such a possibility existed.

PRODUCT:

BOOK GRAPHIC:

Content collection serial:

Red Rover, Very little is known about this apparently single issue, unnumbered publication.

BOOK TEXT:

Content novel, pocket book:

God’s little acre, Writ., E. Caldwell. Anglo-American Publishing Co. Ltd. 1948. Reprinted in Canada.

PERIODICAL GRAPHIC ANTHOLOGY:

| Captain Marvel Comics …. Two colour cover. Black & white interior. | |||

| 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

| 1-1, January

1-2, February 1-3, March 1-4, April 1-5, May 1-6, June 1-7, July 1-8, August 1-9, September 1-10, October. |

2-1, January

2-2, February 2-5, May. 2-6, June 2-7, July 2-8, August 2-9, September |

3-5, May

3-8, August 3-9, September 3-12, December |

4-2, February

4-3, March 4-4, April 4-5, May 4-8, August |

| Freelance … Two colour cover. Black and white interiors. | ||||

| 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

| 1-1, July/August

1-2 ,Sept./Oct. 1-3, Nov./Dec. |

1-4, Jan.

1-5, Feb. 1-6, March. 1-7, April 1-8, May 1-9 July 1-10, Sept./Oct. 1-11, Nov./Dec. |

1-12, Jan./Feb.

2-1, March/April 2-2, May/June 2-3, July/August 2-4, Sept./October 2-5, Nov./Dec. |

2-6, Jan./Feb.

2-7, March/April 2-8, May/June 2-9, July/August 2-10, Sept./Oct. 2-11, Nov./Dec. |

2-12, Jan./Feb.. |

Freelance/Robin Hood, 3-1, March/April 1945. Two colour cover. Black and white interiors.

Freelance, 3-2, May/June 1945, Two colour cover. Black and white interiors. Reverts to all “Freelance” stories.

| Freelance/Robin Hood, Colour cover & interior. | |||

| 3-27, July/Aug. 1945.

3-28, Sept./Oct. 1945 |

. | 3-29, Nov./Dec. 1945

3-30, Jan./Feb. 1946. |

Freelance and Robin split to separate titles again. |

| Freelance, Colour cover & interior. | ||

| 3-31, April 1946.

3-32, June/July 1946. |

3-33, August/September 1946.

3-34, October/November 1946. |

3-35, December1946/Jan. 1947 |

| Grand Slam Comics, Two colour cover & black and white interior. | |||

| 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

| 1-4, March

1-5, April 1-6, May 1-8, July |

2-2, January

2-3, February 2-4, March 2-5, April 2-7, June 2-8, July 3-1, December |

3-2, January

3-10, September 3-11, October 3-12, November |

4-2, January

4-3 February 4-4, March 4-6, May 4-7, June |

| Grand Slam/3 Aces Comics …. Colour cover & interior. | ||

| IV-45, August 1945.

IV-46, September 1945. IV-48, November 1945. |

IV-49, December 1945.

IV-50, January 1946

|

Grand Slam and 3 Aces split to separate titles again. |

| Grand Slam …. Colour cover & interior. | ||

| V-51, February 1946. | V-53, June/July 1946.

5-54, August/September 1946. |

5-55, October/November 1946.

5-56, December/January 1946. |

| Robin Hood …. Two colour cover. Black and white interior. | ||

| 1-6, Dec./January. 1942

1-10, August/September 1942 |

2-2, May/June 1943

2-3, July/August 1943 |

2-10, September/October 1944

2-11, November/December 1944 2-12, January/February 1945 |

| Go to Freelance/Robin Hood | ||

| Robin Hood …. Colour cover & interior. | |

| 3-31, June/July 1946.

3-32, August/September 1946 |

3-33, October/November 1946.

3-34, December 46/January 1947 |

| Spy Smasher Comics …. Two colour cover. Black & white interior. | |||

| 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

| 1-1, June | 1-9, April

1-12, July |

2-6, January

2-12, July 3-3, October 3-4, November |

4-8, March

4-9, April 4-10, May |

| Go to Whiz & Spy Smasher | |||

| 3 Aces Comics …. Two colour cover. Black and white interior. | |||

| 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

| 1-2, January/February

1-3, March 1-5, May 1-6, June 1-8, September. 1-9, October. |

2-1, February

2-2, March 2-3, April 2-4, May 2-5, June 2-6, July 2-8, September |

3-3, April

3-6, July 3-8, September 3-11, December |

4-1, February

4-2, March 4-5, June

|

| Go to: Grand Slam/3 Aces Comics, | |||

| 3 Aces Comics …. Colour cover & interior. | |||

| V-51, Feb. 1946. | V-52, May/June 1946. | V-53, July/Aug. 1946 | END |

| Whiz Comics …. black and white interiors. | |||

| 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

| 1-3, March

1-5, May 1-11, November |

2-1, January.

2-3, March 2-4, April 2-6, June 2-9, September |

3-2, February

3-8, August 3-10, October 3-11, November 3-12, December |

4-1, January

4-3, March 4-6, June. |

| Whiz / Spy Smasher Comics …. Two colour cover. Black and white interior. | |||

| 4-8, August 1945. | 4-8 [9], September 1945. | 4-10, October. 1945. | END |

MERCHANDISE:

Portrait of Freelance for 10 cents.

Glo-crests at 15 cents each:

Characters included Freelance, Purple Rider, Commander Steel, Crusaders, Terry Kane, Hurri-can (a

car), Dr. Destine, Capt. Marvel, Red Rover, Kip Keene. See advertisement in GALLERY.

Transfers at 15 cents each:

Set 1 included: Purple Rider, Dr. Destine, Beverly, Red Rover, Knuckles, Rugged, Commander Steel,

Crusaders, Freelance & Big John, Terry Kane, Robin Hood & Co., Kip Keene, and others.

Set 2 included: Capt. Marvel, Billy Batson, Terry Kane, Tomato, Purple Rider, Spy Smasher, Red

Rover, IBIS, Bulletman and others.

SOURCE:

Article book:

Canuck Comics. Ed., John Bell. Montréal: Matrix Books, 1986: “The War Years: Anglo-American

Publishing Ltd.” Writ., Robert MacMillan.

Article periodical:

Three Aces, V-51, Feb. 1946: Inside front cover:

Article newspaper:

Globe and Mail, 23 October 1982: “Whatever Happened to …?” Writ., Peter Harris. Fanfare 7.

Interview:

Multiple interviews with Ed Furness.

Photos:

From Ed Furness.

GALLERY:

Advertisement. Three Aces Comics, 4-5, June 1945: Back cover.

Advertisement. Three Aces Comics, 4-5, June 1945: Back cover.

.